So many folks are wonder what they need to do to make a career of User Experience Design. As someone who interviewed many designers before, I’d say the only gate between you and a career in UX that really matters is your portfolio. Tech moves too fast and is too competitive to worry about tenure and experience and degrees. If you can bring it, you’re in!

That doesn’t mean school is a waste of time, though. Some of the best UX Design candidates I’ve interviewed came from Carnegie Mellon. We have a UX Research intern from the University of Texas on staff right now, and I’m blown away by her knowledge and talent. A good academic program can help you skip a lot of trial-by-fire and learning things the painful way. But most of all, a good academic program can feed you projects to use as samples in your portfolio. But goodness, choose your school carefully! I’ve also felt so bad for another candidate whose professors obviously had no idea what they were talking about.

Okay, so that portfolio… what should it demonstrate? What sorts of samples should it include? Well, that depends on what sort of UX Designer you want to be.

Below is a list of to-dos, but before you jump into your project, I strongly suggest forming a little product team. Your product team can be your your knitting circle, your best friend and next-best-friend, a fellow UX-hopeful. It doesn’t really matter so long as your team is comprised of humans.

I make this suggestion because I’ve observed that many UX students actually have projects under their belt, but they are mostly homework assignments they did solo. So they are going through the motions of producing journey maps, etc., but without really knowing why. So then they imagine to themselves that these deliverables are instructions. This is how UX Designers instruct engineers on what to do. Nope.

The truth is, deliverables like journey maps and persona charts and wireframes help other people instruct us. In real life, you’ll work with a team of engineers, and those folks must have opportunites to influence the design; otherwise, they won’t believe in it. And they won’t put their heart and soul into building it. And your mockups will look great, and the final product will be a mess of excuses.

So, if you can demonstrate to a hiring manager that you know how to collaborate, dang. You are ahead of the pack. So round up your jackass friends, come up with a fun team name, and…

If you want to be a UX Researcher,

Demonstrate product discovery.

- Identify a market you want to affect, for example, people who walk their dogs.

- Interview potential customers. Learn what they do, how they go about doing it, and how they feel at each step. (Look up “user journey” and “user experience map”)

- Organize customers into categories based on their behaviors. (Look up “personas”)

- Determine which persona(s) you can help the most.

- Identify major pain points in their journey.

- Brainstorm how you can solve these pain points with technology.

Demonstrate collaboration.

- Allow the customers you interview to influence your understanding of the problem.

- Invite others to help you identify pain points.

- Invite others to help you brainstorms solutions.

If you want to be a UI designer,

Demonstrate ideation.

- Brainstorm multiple ways to solve a problem

- Choose the most compelling/feasible solution.

- Sketch various ways that solution could be executed.

- Pick the best concept and wireframe the most basic workflow. (Look up “hero flow”

- Be aware of the assumptions your concept is based upon. Know that if you cannot validate them, you might need to go back to the drawing board. (Look up “product pivoting”)

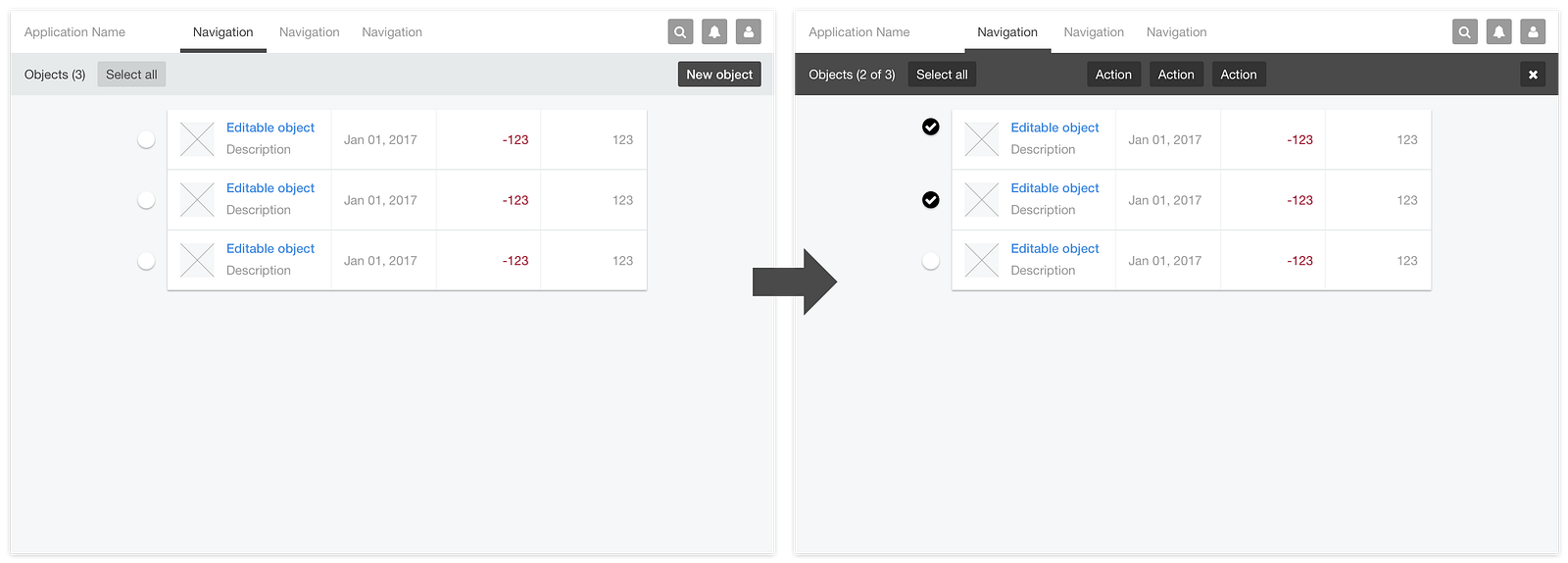

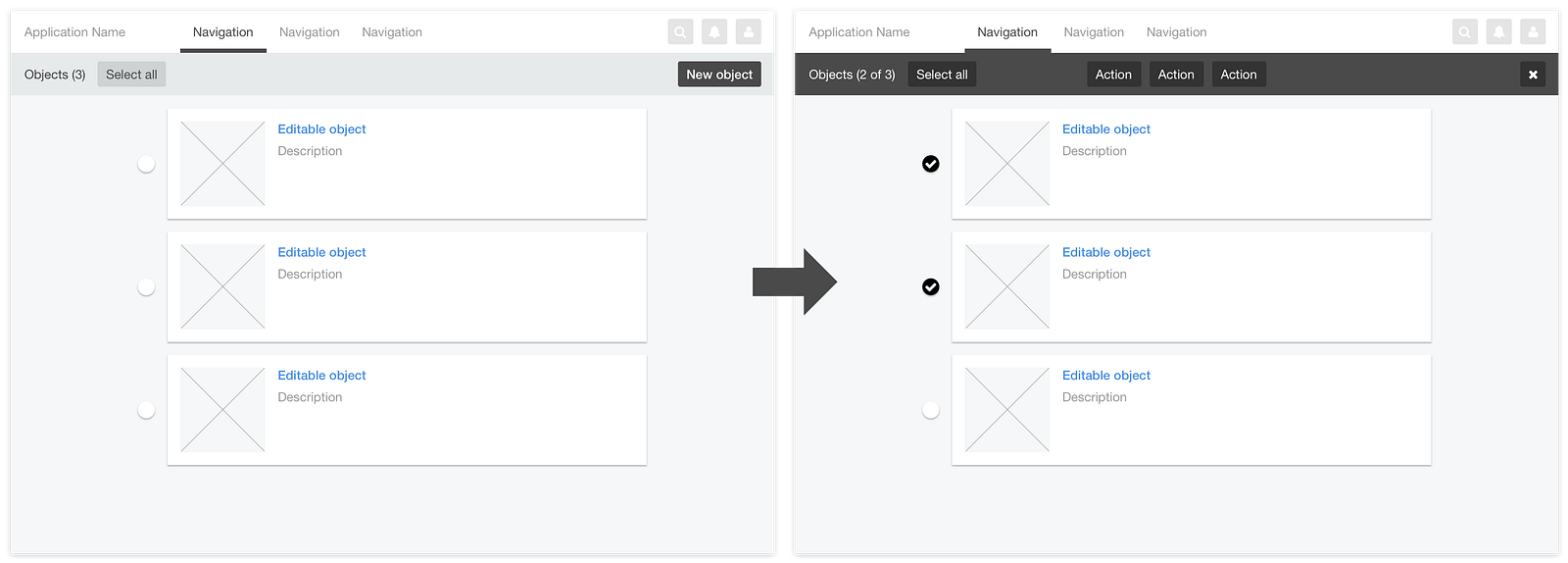

Demonstrate collaboration.

- Invite other people to help you brainstorm.

- Let others vote on which concept to pursue.

- Use a whiteboard to come up with the execution plan together.

- Share your wireframes with potential customers and to see if the concept actually resonates with them.

If you want to be an IX Designer and Information Architect,

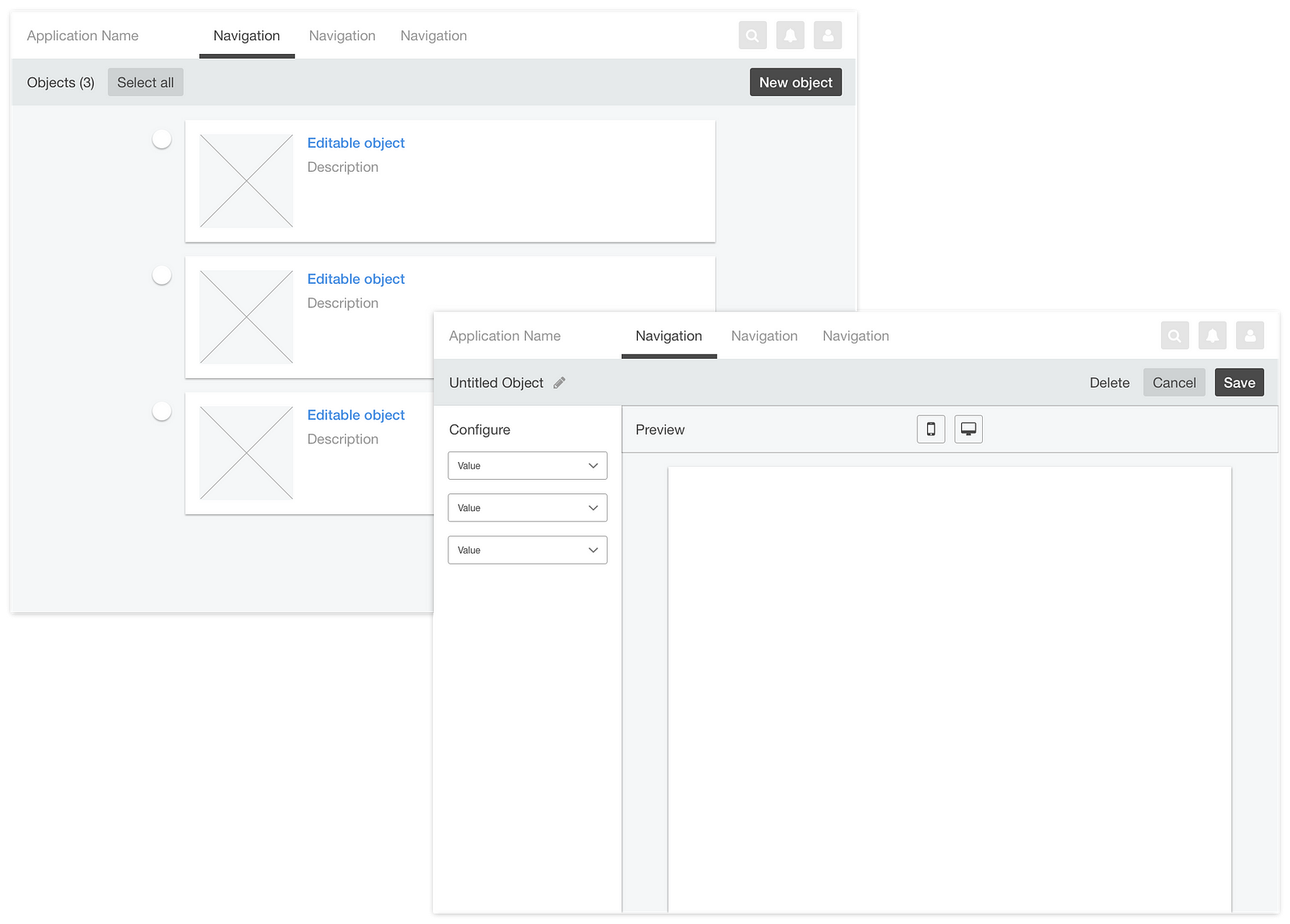

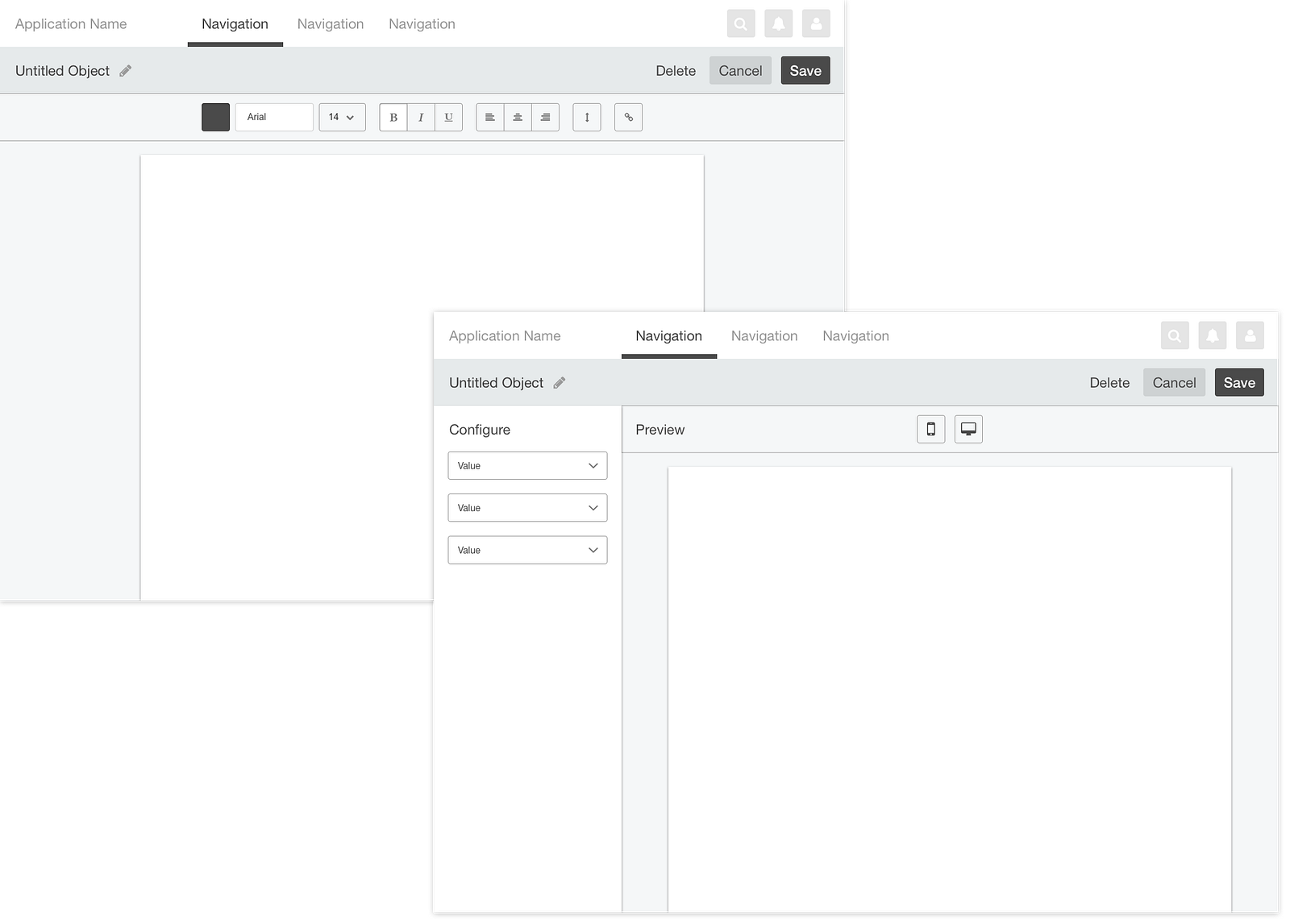

Demonstrate prototyping skill.

- Build a prototype. The type of prototype depends on what you want to test. If you are trying to figure out how to organize the screens in your app, just labeled cards would work. (Look up “card sorting). If you want to test interactions, a coded version of the app with dummy content is nice, but clickable wireframes might be sufficient.

- Plan your test. List the fundamental tasks people must be able to perform for your app to even make sense.

- Correct the aspects of your design that throw people off or confuse people.

Demonstrate collaboration.

- Allow customers to test-drive your prototype. (Look up “usability testing”)

- Ask others to help you think of the best ways to revise your design based on the usability test results.

If you want to be a visual designer,

Demonstrate that you are paying attention.

- Collect inspiration and media that you think your customers would like. Hit up dribbble and muzli and medium and behance and google image search and, and, and.

- Organize all this media by mood: the pale ones, the punchy ones, the fun ones, whatever.

- Pick the mood that matches the way you want people to feel when they use your app.

- Style the wireframes with colors and graphics to match that mood.

- Bonus: create a marketing page, a logo, business cards, and other graphic design assets that show big thinking.

Demonstrate collaboration.

- Ask customers what media and inspiration they like. Let them help you collect materials.

- Ask customers how your mood boards make them feel, in their own words.

Whew! That’s a lot of work! I know. At the very least, school buys you time to do all this stuff. And it’s totally okay to focus on just UX Research or just Visual Design and bill yourself as a specialist. Anyway, if you honestly enjoy UX Design, it will feel like playing. And remember to give your brain breaks once in a while. Go outside and ride your bike; it’ll help you keep your creative energy high.

Hope that helps, and good luck!

This article was originally published on Medium, “How to I break into UX Design?“